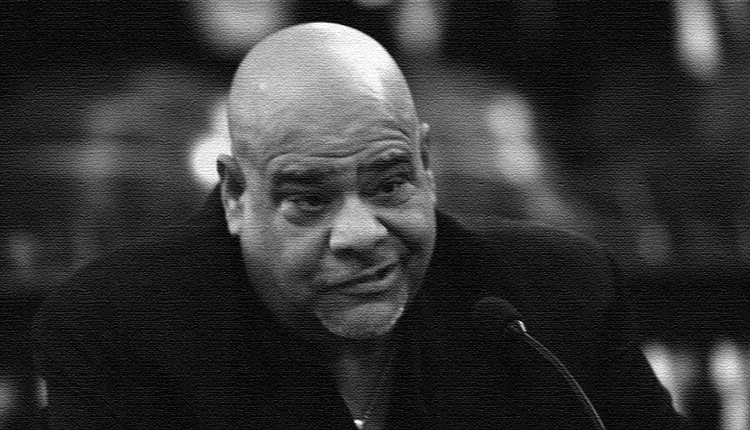

They called him the Fat Rat, but he didn’t really care.

Ron Previte always knew who he was and what he had done. And he was okay with that, which made him unique in the underworld and immune to the slurs and epithets other wiseguys threw at him.

For him, it was a game and he always thought he knew how to play it better than they did.

It wasn’t about right or wrong, about morals or ethics. When it came to crime, he was totally amoral. He would smile and say he was a “general practitioner.” He did it all.

And becoming an informant, first for the New Jersey State Police, and then for the FBI, was part of his practice.

Previte died two months ago. He had been sick for over a year, battling various ailments that eventually led to a fatal heart attack. He was 73.

“What would you have bet that it would have been a heart attack that took him out?” an FBI agent asked at Previte’s memorial service. A dozen other law enforcement officials standing in the back of the funeral parlor down in Hammonton, NJ, that night nodded and smiled.

Nobody figured he would die of natural causes.

Ronnie Previte lived life on the edge and most people figured that he would die out there taking another chance, trying to make one more score.

Despite the fact that he wore a body wire for over a year, recorded hundreds of conversations and testified openly in federal court, Previte opted not to enter the Witness Security Program. He never left.

Hammonton was his base when he was on top of his game, and he stayed in that general area, still visiting friends and still poking around on the fringes of the criminal underworld.

After he died, some of his detractors took offense at the stories that were written about him, claiming he was made to look like a hero when in fact the only reason he had cooperated was he didn’t want to go to jail.

“He didn’t man up,” said one.

Previte, of course, didn’t see it that way. It wasn’t about going to jail, it was about beating the system, whether that system was law enforcement or the mob. He was a survivor, a guy whose only loyalty was to the person he saw staring back at him in the mirror each morning.

And he was okay with that.

Didn’t man up?

He strapped on a body wire almost every day for over a year and met and did deals with individuals who, had they known he was wired, would have taken him out. That, to Previte, was manning up.

The fact of the matter was, he didn’t like or respect most of the people he was helping the FBI target. Wasn’t all that crazy about some of the FBI agents either, but that’s another story. He had his own idea of what organized crime was supposed to be. And it wasn’t what he experienced when he first connected with mob boss John Stanfa in the early 1990s. Nor was it any better when, amazingly, he was able to segue over to the anti-Stanfa faction after Stanfa and two dozen of his top associates were indicted and taken off the streets.

The mob, the Mafia, Cosa Nostra, was a thing of the past, he said.

“You’d have to be Ray Charles not to see it,” was the way he put it.

Previte always had a way with words.

He was erudite. He read books. He studied history. Conservative to an extreme, he would frequently wax philosophically, but then drift into a racist or bigoted commentary. That’s who he was.

I first met him when he was around Stanfa. I had written several stories about the entourage, the “palace guard” that always seemed to accompany the Sicilian-born mob boss after he took control of the Philadelphia crime family in 1990.

One of the members of that entourage was a burly six-foot, three-pound ex-Philadelphia cop—Ron Previte. I was a reporter at The Inquirer at the time. One afternoon I was sitting at my desk in Cherry Hill when the phone rang. I picked it up and heard this:

“George Anastasia? This is Ron Previte. You seem to have an interest in my life. I’d like to meet you.”

I said fine, as long as it was in a public place and during the day.

One afternoon later that week I was in the Silver Coin Diner in Hammonton having lunch with Ron Previte. He was already cooperating at that time, but I didn’t know it. Over the course of the next three years, through the bloody mob war that pitted the Stanfa faction against another group headed by Ralph Natale and “Skinny Joey” Merlino, Previte would offer insights and commentary about what was going on. A lot of it worked its way into the stories I was writing.

“Some day you’ll write a book about me,” Previte said after we had gotten to know each other and he had detailed his extensive life in crime. I said I didn’t think that was possible. He had told me stories about his involvement in gambling, extortion and bribery. He had also dabbled in drugs and prostitution, at one point running a brothel in Center City that catered to high end clients, lawyers and wealthy businessmen.

“I write about all that, you’ll go to jail,” I said.

Previte smiled.

“Don’t worry,” he said. “We’ll work it out.”

And we did.

After his tapes led to the indictments of Natale, Merlino and nearly a dozen others, his role as a cooperating witness became public. I covered every trial at which he testified and then I wrote that book. It was called The Last Gangster.

Here’s how I had described him early in the story:

“Previte doesn’t claim that God, morality or a sense of righteousness led him to do what he did…It was simply a question of survival…(He) had aspired to be a made member of the organization. He saw it as the pinnacle, the top of his profession. When he got there, though, he was disillusioned. Honor and loyalty had been replaced by greed and treachery. The sense of family that supposedly governed the actions of men of honor was gone. Instead, it was every man for himself.

“Previte cut his deal with the government because it was the smart, the sensible, the logical thing to do. He makes no apology for it.”

The book was published in 2004. Thirteen years later, as Previte struggled with the ailments that would lead to his death, he said he wouldn’t change a thing.

“I can’t complain,” he said in one of the last conversations we had a few weeks before he died. “What’s the point? I did a lot of things and I did them on my own terms. How many people can say that?’

Not many.

Previte took pride in that.

And if he was listening, I’m sure he got a kick out of the way they ended his memorial service. There were about a hundred people in the funeral parlor that night, including a dozen law enforcement types who had worked with him at one time or another.

They heard a cousin talk about how, while he didn’t often know how to express it, Previte loved his daughters, his grandsons and other members of his family. They heard one of his sisters talk about how when she was a nervous and anxious first grader at Our Lady of Lourdes in Southwest Philadelphia, she always felt better when she looked out her classroom door and saw her big brother, Ron, standing in the hallway waving at her.

Ron Previte was in eighth grade at the time. It was only later, his sister said, that she learned the reason he was in that hallway so often was that he had been kicked out of his class for disciplinary reasons.

Everyone nodded and smiled at the story.

Then the funeral director said the service would end with a song. And with that the room filled with Frank Sinatra singing “My Way.”