In certain circles, he was known as “The Godfather of Rock and Roll.”

It wasn’t always meant as a compliment.

From the 1950s through the late 1980s he was a force to be reckoned with in the American music industry. He made millions for himself and his “associates.”

He was an entrepreneur, a philanthropist and a gangster.

And he seemed to enjoy each role.

Morris Levy died in 1990 shortly before he was to begin a 10-year prison sentence following his conviction in an extortion case that included members of the Genovese and DeCavalcante crime families. The fact that he was friends with several high-profile mob figures was never in dispute.

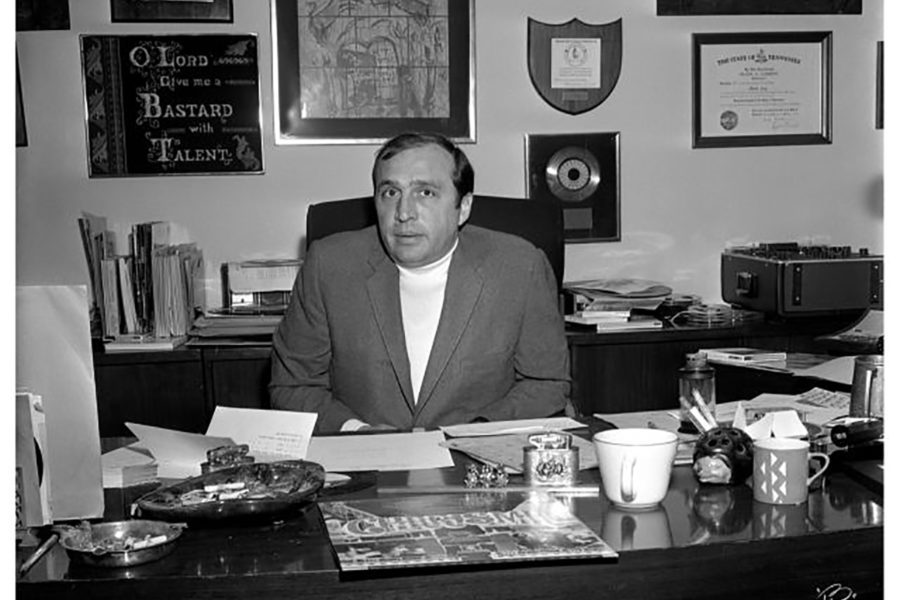

Sitting in his midtown Manhattan record company office in June of 1987 shortly after being indicted in the extortion case, he offered his standard reply when asked about his alleged mob ties.

“I’ve been on Broadway 47 years,” said Levy. “I know some of these characters and some I like very much…I knew Cardinal Spellman, too. That don’t make me a Catholic.”

It sounded like a line from Guys and Dolls, which was the image Levy clearly was going for. But the reality was his role and connections were more Goodfellas.

Some of that is touched on in a new book about one of the most notorious attempted shakedowns in Levy’s long music industry career. The target was John Lennon who was recording on his own after the break-up of The Beatles.

Lennon, the Mobster and the Lawyer is written by attorney Jay Bergen who represented Lennon in his 1975 legal battle with Levy. The dispute revolved around recording rights and a bootleg album of rock-and-roll songs by Lennon.

Levy, no surprise, was the bootlegger.

He claimed he had an agreement to market an album called “Roots” that he had fashioned after gaining access to some preliminary and less than quality tapes of Lennon performing classic rock and roll songs. At the time, Lennon was preparing an album called “Rock ‘n’ Roll.” The litigation ended with an almost across-the-board win for Lennon and the legitimate companies for whom he recorded, Capitol/EMI and Apple Records.

Bergen’s book is heavy on legalese and includes extensive chunks of Lennon’s courtroom testimony, transcripts that are sure to be fascinating for any Beatles fan. What gets lost in the telling is the underworld significance of the courtroom victory.

Levy had been taking advantage of recording artists for years, often claiming songwriting credits in order to grab millions of dollars in royalties that were due the actual singer-songwriters. He used fear and intimidation—and his mob connections—to keep those artists in line. Lennon was the one of the few to successfully challenge him.

Lennon’s status as a veritable icon in the industry may have been the reason Levy never took his case beyond litigation. Other entertainers weren’t as lucky. According to another lawsuit brought after his death, Levy once warned a singer who was complaining about overdue songwriting royalties, “Don’t come down here anymore or I’ll have to kill you or hurt you.”

In that case, Levy had taken songwriting credit for the classic 1950s hit “Why Do Fools Fall in Love.” The artists who wrote and recorded the song said they had received just $1,000 in royalties for a record that sold over three million copies. They eventually won a $4 million judgment against Levy’s estate.

Like so many others, they waited until Levy was dead before making their claim. To do so while he was alive would have been courting disaster.

Bergen accurately describes Levy as “a music industry grifter who regularly cheated artists” and as someone who “would not know an F-sharp from an A-flat.” But what Levy did know was the music business—at least the business as it existed in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, when airtime on popular radio stations could make or break a new recording and when payola was the standard coin of the realm.

Tommy James, a high-profile rock-and-roll star in the 1970s, detailed a lot of that in his book, Me, the Mob and the Music, which was published in 2010.

James credits Levy with launching and steering his career. But he acknowledged in an interview shortly after his book came out that, “Getting your money was like taking a bone from a Doberman. It just wasn’t going to happen.”

Another industry source tells a story about Levy negotiating royalty rights with an artist. Levy agreed to give the singer a substantial percentage. An associate, who was present when the deal was struck, later asked Levy why he had been so generous. “What’s the difference?” Levy replied. “I’m not going to pay him.”

Authorities had been aware of Levy’s mob connections for years. His ties to the Genovese crime family, first to mob boss Tommy Eboli and later Vincent “The Chin” Gigante, were outlined in an FBI affidavit that surfaced in the federal court case in Camden that brought Levy down.

“An FBI investigation has shown that since before 1963 Morris Levy has been a lucrative source of cash and property for leaders of the Genovese LCN family,” the affidavit reads in part. Levy’s dealings, the document alleged, had been “primarily through and for the benefit of (Gigante) to whom Levy has passed large cash payments, property and shares in Levy’s recording enterprises.”

Authorities suspected that the Genovese crime family had a big piece of all of Levy’s action, which at various times included a chain of record stores called Strawberries and several record companies, including Roulette Records, the company for which many of Levy’s recording artists worked.

Levy’s empire came undone in the late 1980s after he and two mob figures, Genovese crime family capo Dominick “Baldy Dom” Canterino and New Jersey DeCavalcante crime family soldier Gaetano “Corky” Vastola, were charged in an extortion and shakedown scheme in which a wholesale record distributor named John LaMonte was targeted. The convoluted case included allegations that Levy and his mob associates had insinuated themselves into a $1.2 million deal between LaMonte and MCA records, at the time a major Los Angeles entertainment company.

LaMonte, according to a federal indictment, had agreed to purchase 60 tractor-trailer loads of “remainder “records and cassettes. For readers old enough to remember, these were products found in remainder or wholesale bins at record stores back in the day when cassettes and record stores existed.

LaMonte, of Darby, PA, balked at paying, claiming that Levy and his associates had “creamed the load,” that they had taken all the best titles before LaMonte received delivery. He was badly beaten by mob figures working for Levy and Canterino and, after being treated for a fractured eye socket, he agreed to cooperate with the FBI.

The case that played out in federal court in Camden offered a look inside organized crime’s involvement in the entertainment industry and spawned several books. Among the best is Stiffed, a True Story of MCA, the Music Business and the Mafia by Bill Knoedelseder.

Levy is also the title character in Godfather of the Music Business by Richard Carlin and is one of the principal figures in Dark Victory, Ronald Reagan, MCA and the Mob by Dan Moldea. More recently, Levy was the prototype for Hesh Rabkin, Tony Soprano’s entrepreneurial Jewish mob associate in the long-running HBO hit.

Like Levy, Rabkin (played by actor Jerry Adler) was a music industry impresario, and like Levy, he had a horse farm. Levy’s 1,400-acre farm, near Albany, NY, was part of a sprawling real estate empire in which, authorities alleged, the mob held a secret interest.

The FBI affidavit in the Camden case cited an informant‘s claim that Gigante had a “stranglehold on Morris Levy’s record industry enterprises, in effect turning Levy into a source of ready cash” for the Genovese crime family and that Levy was an “earner” who provided “cash for Gigante’s crew to buy real estate.”

A small piece of that cash, no doubt, was generated by “Roots,” the bootleg rock-and-roll album that John Lennon went to court to discredit. Perhaps the most famous Beatle of them all, Lennon was ahead of his time in challenging Levy and, because of his status, never had to deal with the violence, fear and intimidation visited on many others who crossed the Godfather of Rock and Roll.

Five years after winning his battle with the mobster, Lennon was the target of a different kind of American violence.