Think back to people who spent several decades around the Philadelphia sports scene and the names Connie Mack, Bill Campbell, Richie Ashburn, Harvey Pollack, and Sonny Hill may pop into your mind. Ditto Bobby Clarke, Larry Bowa, Dave Zinkoff and Dan Baker, who is still going strong as the Phillies’ public address announcer. Or Eagles broadcasting legend Merrill Reese.

Only one man, however, can say he was part of a Philadelphia sports franchise when it started and has stayed with the team continuously—and is still there 51 years later.

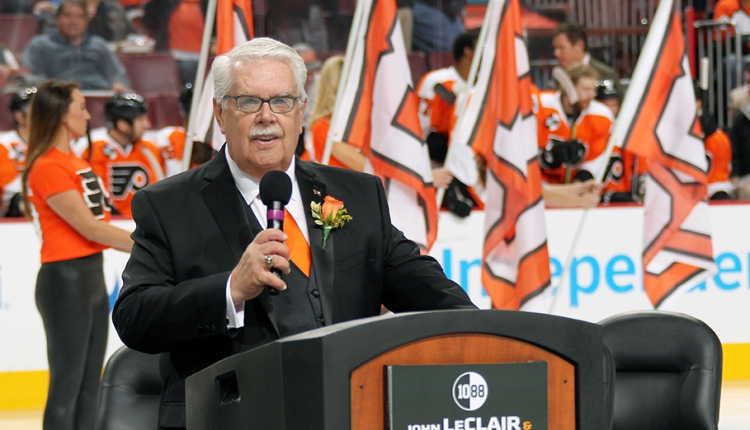

Say hello to Lou Nolan, the Flyers’ congenial and sharp-witted public-address announcer.

Nolan was there for the Flyers birth in 1967 and has been the P.A. announcer for the good (two Stanley Cup seasons, the epic win over the Russians), the bad (a goal allowed with four seconds left in their season, costing them a playoff spot) and the ugly (fans throwing give-away bracelets onto the ice during a playoff loss).

Lou and I recently co-authored his unofficial diary of his half century with the Flyers in “If These Walls Could Talk: Philadelphia Flyers,” a 236-page book that takes you behind the scenes at the Spectrum and the Wells Fargo Center, Nolan’s unofficial second and third homes over the years.

Below are some excerpts from the book, printed with the permission of Triumph Books. The book is available at local stores and at www.triumphbooks.com/WallsFlyers.

The following excerpts are Nolan’s words, as told to me. – Sam Carchidi

Excerpts from “If These Walls Could Talk: Philadelphia Flyers” by Lou Nolan and Sam Carchidi

For a lot of years, selling securities to banks has been my real job. But my most rewarding job has been the one that, for a half century, has taken me inside a noisy, percolating South Philadelphia hockey arena during the fall, winter, and spring months.

I have been fortunate enough to have been with the Flyers since their inception in 1967—first as a public-relations assistant to Joe Kadlec, and then, since 1972, as their public address announcer.

It’s a career that has been fulfilling, exhilarating, and unpredictable.

Lou Nolan in the Flyers locker room after winning the Stanley Cup

Witness my first game as public-address announcer. There I was, minding my own business and sitting between two players who went to the Spectrum penalty box during a preseason game. They were yapping at each other as they sat down when, suddenly, the visiting player picked up a bucket of ice and heaved it at our guy, Bob Kelly, who was one of our feisty wingers.

The ice never reached the player they called Hound. Instead, it bounced off the side of my head and drenched my sport coat as the fans sitting behind us let out a collective roar.

In a way, it was my baptism into the NHL. Instead of holy water, I got christened with ice water. Hey, just part of the job. Part of what has been an incredible journey.

The Flyers finished with their first winning record in franchise history during my first year as the P.A. announcer, and that started an amazing stretch during which Philadelphia fell in love with the Orange and Black.

I have witnessed some great moments along the way: eight trips to the Stanley Cup Finals, consecutive championships in 1974 and 1975, an epic win over the Soviet Red Army team, and key games in the remarkable 35-game unbeaten streak in 1979–80. And who could ever forget our Cinderella run to get to the 2010 Finals?

But it hasn’t been all glitz and glamour.

When the Flyers franchise was awarded, Ed Snider and Jerry Wolman were taking a huge risk. You see, I was in the minority—a die-hard hockey fan who had followed the old Philadelphia Ramblers, who played at the Philadelphia Arena in the Eastern Hockey League.

At that time, however, most Philadelphians knew little about hockey.

Across the bridge at the Cherry Hill Arena, the Jersey Devils were playing in the Eastern Hockey League. They were the lone survivors of seven failed Philadelphia-area, minor-league teams over a 38-year period.

But in 1966 (a year before we started playing), Philly landed a franchise at a cost of $2 million, in part because of plans to build a new rink, the Spectrum. That helped offset the fact that Philadelphia was the only one of six new NHL franchises not to have a high minor-league affiliation.

The team was named “Flyers” by Ed Snider’s sister, Phyllis. That was the easy part. The tough part: attracting fans in a city with deep baseball, football, and basketball roots. In addition, several months of hockey’s schedule overlapped with the immensely popular Big Five basketball scene.

In 1967, a parade to welcome the team was held down Broad Street. About 25 people showed up. As defenseman Joe Watson is fond of saying, there were more Flyers personnel in the parade than there were people watching it.

Today, virtually all home games are sellouts and the Flyers have become a huge part of Philadelphia’s sports landscape. But in 1967–68, there were growing pains. Lots and lots of growing pains. We lost our first exhibition game 6–1—to a minor-league team. Well, at least it was our minor-league team, the Quebec Aces.

The regular-season home opener drew 7,812 fans, and we eked out a less-than-artistic 1–0 win over the Pittsburgh Penguins as Bill Sutherland scored the goal, Doug Favell recorded the shutout, and public-address announcer Gene Hart kept the spectators informed as he explained the icing and offside calls. I announced the goal scorers

And penalties to those who sat in our scarcely filled press box. Today, in the Information Age, there may be 50 to 75 media types at our games. Back then, you could count the reporters on one hand.

I also kept handwritten stats during the season—remember, this was way before computers—and handed them out to reporters after the game. My Catholic school penmanship, drilled into me by the nuns, was actually paying off.

I got the job, which was part-time, partly because of my friendship with Joe Kadlec. Joe had been working for the Daily News sports department and was hired as the Flyers’ first public-relations director.

I had met Joe the previous year down in Margate, NJ. We were young, single, and carefree, and we partied and chased women together.

To be honest, I found out about the Flyers because of a big billboard on Route 42 in South Jersey that read, “The Flyers Are Coming!” I looked into it because I had a little bit of a background in hockey. The goal judge for the Ramblers—a team that was here from 1955 to 1964—was a guy named George Lennon. George was the uncle of a classmate of mine in grade school, also named George Lennon. We used to go to the games with his uncle on Friday nights at the arena on 45th and Market. We’d watch the games and run around the rink. We’d get the broken sticks, take them home, and tape them up and play street hockey behind the school. We did that for years. We’d put on our shoe-skates—you put the skates on your shoes—and we’d play all the time.

As I mentioned, I was a rarity at that time. I was hooked on hockey even though we didn’t have our own NHL team. I lived in a Southwest Philadelphia row home at the time, and I’d take the 36 Trolley downtown to buy hockey books. I’d watch the Original Six teams—Montreal, Boston, Toronto, Detroit, Chicago, and the New York Rangers—on TV and I just loved the sport. I got to know the league and read all the hockey books, which they only sold at 13th & Market. And then one day when I was talking to Joe, he told me he just got the job with the Flyers as the PR director. I said, “Hey, if you need any help, I’d be glad to help you. I know a little bit about the sport.” Joe told me to come to this cocktail party where they were celebrating the team’s arrival. Joe was a North Catholic guy and I was a West Catholic guy, but we became buddies down Margate through some mutual friends.

It’s strange how your life can take a turn by fate. I’m sure everybody can look back to an unscripted event that changed their lives in some way. For me, if it wasn’t for some friends bringing Joe and me together, I probably would never have been a part of the Flyers.

I would see our owner, Ed Snider, in locker rooms after games in our first year. That was a tradition that started in 1967 and continued until he passed away in 2016. He always loved being around the players, loved getting to know them and finding out about their families and their lives. Ed wasn’t just some corporate guy whom the players never saw. The franchise was his baby and he was totally immersed in it, and it showed in his deep respect and admiration for the players.

Back in our first year, I would see the guys from the group who ran the team—Ed, Joe Scott, and Bill Putnam. They were all excited about making the Flyers become a big part of Philadelphia.

I always called Ed by his first name, but to some—like Bob Clarke—he was always Mr. Snider. And when I got the P.A. job, Ed would call me on my phone in the box if things got really strange down on the ice. He never called me if he agreed with a call, but he’d call me if he wanted a clarification on something that happened. A lot. He might ask me why one of his players was getting a penalty or what it looked like from my level on the ice. I would say, “I don’t quite understand it, Ed. I know what you mean.” But I would never say that to the referee. I had to stay professional with the ref.

I remember one game when there was a huge brawl, and Bob Myers was the ref. He came over to me and started telling me all the penalties he was handing out so I could announce them. This went on for a while because there were a lot of penalties. Just then, the phone rang and it was Ed. I said, “Just a minute, Ed,” and I put the phone down because Myers wanted to finish up. When Myers finished, I got back on the phone with Ed. He said, “Lou, there’s something you and I have to get straight between us.” I said, “Sure, Ed, what’s that?” And he said, “When I call you, I want the referee put on hold.”

That was Ed. He just wanted to blow off some steam. Everybody used to kid me that I was on his speed dial from his suite.