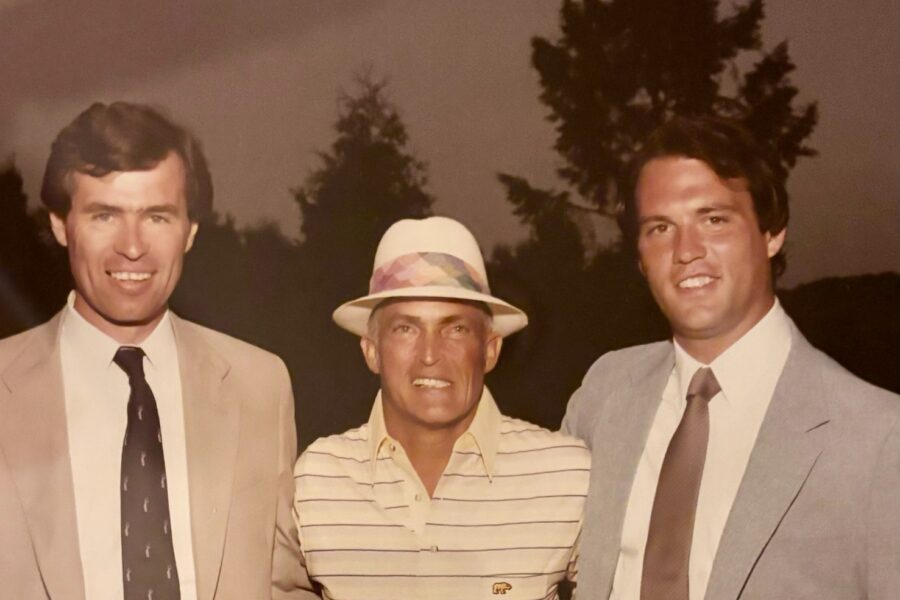

After playing in the Getty Celebrity Pro-Am at Cavaliers Country Club in 1982, my friend John Riley and I were approached by Dave Press, the local public affairs director for Getty. (John is a former captain of the University of Delaware golf team and has recently published biographies on the life of local golf greats Porky Oliver and Bill Hyndman.) Press shared with us that Getty had been spending about $25,000 a year and raising far less for the designated charity, the Leukemia Society of America. He was worried that the event could not be sustained and wondered if we might like to get involved.

The Getty tournament was fairly unique at the time, with golfers paying to play with a local or national sports figure. John and I thought it had significant potential both as a charitable fundraiser and as a venue for corporate client entertainment. We also saw it as a chance to bring the PGA Tour to town, something that had rarely happened in Delaware.

We knew we would have to hit a home run the first year, but the fledgling event could not afford an Arnold Palmer or a Jack Nicklaus. (A couple of years later, with the help of his Wilmington dentist Howdy Giles, we would book Palmer.) While still considering the options we thought we could afford, I went to New York for my bi-annual check-up with Dr. Ralph Marcove, who had saved my life when he amputated my arm and shoulder to remove a Desmoid tumor. I mentioned to Marcove what we were trying to accomplish and that we were looking for the right PGA headliner to ensure our success. Without hesitating, he said, “What about Chi Chi Rodriquez?” When I asked if he knew him, he explained that he had operated on him to remove a tumor on his arm. He gave me his number.

At that point in his career, Rodriquez had won eight times on the PGA circuit. He had a hardscrabble upbringing in Puerto Rico but discovered golf through caddying and taught himself the game. His swing was unconventional but generated significant power enabling him to keep up with some of the longest drivers on the pro tour. To the shock of Arnold Palmer’s fans, he beat him by a stroke in 1964 to win the prestigious Western Open. Chi Chi also developed a repertoire of trick shots combined with amusing one-liners which often targeted the “King of Golf” himself.

While Chi Chi could entertain the fans and crack jokes with the best of them, he had a more serious and humanitarian side. To my surprise, when he arrived in Wilmington, he turned down the opportunity to have dinner with Joe DiMaggio and Warren Spahn, telling us he wanted to make certain he was rested and at his best to entertain our patrons the next day. The next morning, he began a long day stationed on a par 3, hitting trick shots and having his photo taken with everyone. Late in the afternoon, he came back to the clubhouse to regroup before he began his famous golf exhibition. John and I were sitting at a table with him when a young girl with Down Syndrome caught his attention.

As we got up to head out to the tee to begin the show (We had skydivers and the Phillie Phanatic timed to appear just before the exhibition!), Chi Chi headed straight towards the girl and spoke softly to her. After a minute or so she removed her apron, and Chi Chi took her by the hand. As we started out the door, he looked at us and said, “This young lady will be my special guest.” He walked out with her and had a seat placed immediately behind the roped-off area, where he announced to the crowd that he was dedicating his golf exhibition to his new friend. The smile never left her face.

The Leukemia Classic went from losing money to reaching $100,000 within three years. Chi Chi set a very high bar in 1983 and even with names like Arnold Palmer, Fuzzy Zoeller, John Daly, and Payne Stewart, I’m not sure we ever matched the joy people felt from rubbing shoulders that day with the wise-cracking man from Puerto Rico. When we lost Chi Chi Rodriquez on August 8, 2024, we lost more far than a golf champion.