Ed Snider’s vision has turned into a lovefest between the Flyers and their fans as the franchise celebrates its 50th anniversary season. Despite not winning a Stanley Cup since 1975, the fans’ loyalty has remained steadfast.

Never was that more evident than when a sellout crowd attended an alumni game between the Flyers and Pittsburgh Penguins at the Wells Fargo Center on Jan. 14. It was a matchup between two of the six expansion teams that entered the NHL in 1967.

The teams played to a 3-3 tie (remember them?) before an appreciative sellout crowd, and the game featured players from every Flyers decade, including the famed “LCB” and “Legion of Doom” lines. Reggie Leach, Bobby Clarke and Bill Barber formed the former, John LeClair, Eric Lindros, and Mikael Renberg the latter.

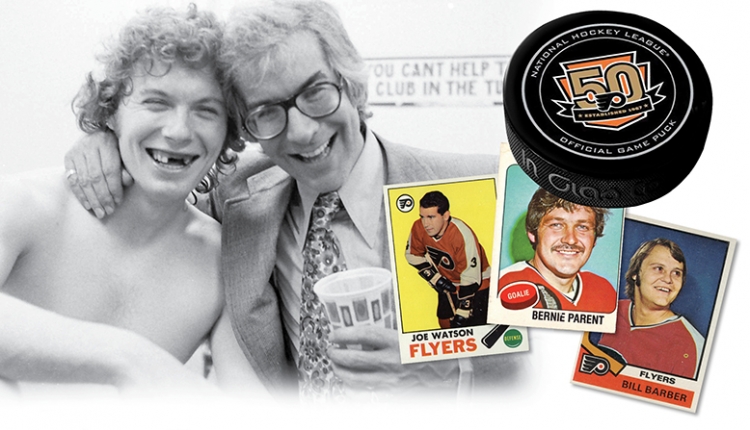

Representation ranged from original Flyer Joe Watson to Danny Briere and Simon Gagne, forwards on the team’s Stanley Cup finalist in 2010.

In honor of their 50-year anniversary, the Flyers have also brought back many of their former stars for pre-game festivities this season, reliving memorable moments.

But while the focus has been on the many heroes who have worn the Orange and Black, there is another group that deserves serious mention.

Eric Lindros recently played in a sold out alumni game vs. the Pittsburgh Penguins as part of the Flyers 50th Anniversary celebration.

“The fans,” Lindros said, “were always incredible in Philly.”

Oh, they may boo on occasion in an attempt to wake up players, but they have filled virtually every seat for the longest of times.

Lindros, who was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in November, never took the fans for granted. When he played, he wanted to reward them for their loyalty. For proof, go to YouTube and watch Lindros, his voice cracking, his eyes filled with tears, in his emotional speech when he accepted the 1994-95 Hart Trophy as the league’s MVP.

“In closing,” he said toward the end of his speech, “I’d just like to say, thank you to the Philadelphia fans who supported us when we weren’t so good.”

And here, Lindros became choked up with tears. After a long pause, he composed himself, barely, and said: “We’re getting better and we’re going to do it.”

The Flyers never won a Cup during the Lindros era. Fact is, they haven’t won one in 42 years. But the fans keep filling the arena.

When Lindros and LeClair were inducted into the Flyers Hall of Fame in 2014, both said the fans pushed their careers to a higher level.

“You guys are awesome,” LeClair told the standing fans before a banner with his name and his former linemate’s was raised to the rafters. “You didn’t accept losing.”

LeClair thanked the fans for “the continuous energy” they gave him.

Lindros had a similar theme.

“Night in and night out, you brought passion to the Wells Fargo Center,” he said.

At the November Hall of Fame ceremony in Toronto, Lindros said, “Philly fans are terrific. They really are. There’s not many cities in the States where you get that feeling. You get it here in Toronto, obviously, and in every Canadian city. I think Philly is top-notch in terms of the U.S. side of things.”

After the alumni game in January, the participants seemed awe-struck by the crowd.

“A sellout to watch a bunch of us has-beens,” goalie Brian Boucher said with a smile. “Can’t say enough about the fans.”

“I wouldn’t have changed anything. I would have played with one leg, to be honest with you,” Hall of Fame left winger Bill Barber said. “To have the opportunity to be out there for our fans, we have the greatest fans in the world and I thank them for that. It was a real pleasure to play here in Philly in front of a crowd like that.”

“It’s all you need to know about Flyers fans,” Briere. “To get 20,000 people to come out for guys that are past their prime. That’s all you need to know. It’s just simply amazing.”

Briere said it was great for him and the other players “to have one more day to live our dream. I still have goosebumps just thinking about it. To get on the ice for the warmup and to see the whole building already full…to play with legends…It was a blast.”

Carl Luzi, 61, who owns an insurance and retirement planning agency in West Berlin, NJ, attended the alumni game with his 26-year-old son, C.J.

The elder Luzi called the game “a real tribute to the organization, including Ed Snider.”

Snider, of course, was one of the team’s co-founders and he was the Flyers’ chairman until his death last April.

“I think the roof would have blown off if 88’s shot had hit the back of the net to win it late in the game,” Luzi added, referring to Lindros. “All in all, it was a life moment for all of us in the Flyers family.”

The loudest cheers may have been when Snider was shown on the scoreboard in a series of photos, a tribute to the man who had the foresight to believe hockey could make it in Philadelphia.

WHEN YOU HEAR all the glowing tributes to the fans, it’s easy to forget that Philly wasn’t always a hockey hotbed.

When Snider co-founded the team, he was taking a huge risk. At the time, Philadelphia did not have a good track record of supporting major- or minor-league hockey teams.

In 1967, after returning from Quebec City and their first training camp, the Flyers tried to drum up fan interest by holding a parade down Broad Street.

About two-dozen people showed up.

“There were more people in the parade than there were people watching it,” said Watson, an original Flyer who is now a senior account executive for the Wells Fargo Center’s advertising department. “I said, ‘Hell, we’re not going to be here very long.’ One fan gave me the finger and said, ‘You’ll be in Baltimore in six months!’ “

The franchise was purchased for $2 million, and Snider and Jerry Wolman got the Spectrum built for $12 million. A bogus contest was held to name the team. The winner was “Flyers,” but Snider’s sister, Phyllis, had actually chosen that name months earlier.

The franchise was purchased for $2 million, and Snider and Jerry Wolman got the Spectrum built for $12 million. A bogus contest was held to name the team. The winner was “Flyers,” but Snider’s sister, Phyllis, had actually chosen that name months earlier.

General manager Bud Poile and coach Keith Allen did an excellent job in the expansion draft, selecting players such as goalies Bernie Parent and Doug Favell, defensemen Watson and Ed Van Impe, and right winger Gary Dornhoefer.

Parent, Watson, Van Impe, and Dornhoefer would become fixtures when the Flyers won consecutive Stanley Cups in 1974 and 1975.

The Flyers were in the West Division with the five other expansion teams. The East Division was composed of teams from the NHL’s Original Six.

Fans were slow to accept the new team. Tickets were $2 to $5.50 per game during that first season, and just 7,812 showed up for the home opener. Gradually, as the Flyers sprinkled in wins against the original teams, attendance picked up. By February, they had their first home sellout.

The Flyers finished 31-32-11 in their first season, were outscored 179 to173, and won the title in the West, which was also composed of expansion teams from St. Louis, Oakland, Pittsburgh, Minnesota, and Los Angeles.

Late in that first season, winds gusting at more than 50 M.P.H. blew off a portion of the Spectrum’s roof, causing the Flyers to play seven “home” games in Quebec City, Toronto, and Madison Square Garden.

“I think the guys rallied around the fact that they were going to be Road Warriors, so to speak, for a long time,” said veteran public-address announcer Lou Nolan, who worked in the team’s public-relations department, headed by Joe Kadlec, during the franchise’s first season.

THE FLYERS HAVE WON just two Stanley Cups in their history, and none since 1975.

But they HAVE been successful. They have missed the playoffs just 10 times and have reached the Cup Finals eight times.

Since they entered the NHL in 1967-68, only Montreal and Boston have a higher points percentage than the Flyers.

That, and the players’ eagerness to live in the community and get involved in local charity events, explains why a sellout crowd attended the alumni game to help celebrate the franchise’s 50th anniversary.

Boucher was asked if he was surprised by the huge turnout.

“I don’t know why I would be shocked because I know how great of a hockey town this is,” he said. “Everybody talks about a sports town; it’s a great hockey town. These Flyers fans, starting right around this time of year, working into February, March….they really get jacked up to watch their Flyers play into the spring.”

Boucher paused.

“I’ve had a couple of opportunities to be a part of teams that did that,” he said. “I know what it’s all about, so I guess that I’m not shocked that 19,000 fans came to watch their heroes of yesterday play because they love the Flyers so much, and it’s a real treat as a player when you’re all done to get another chance to be in the NHL for one night. It was a real special night.”

“I think it’s the only city in the league that would do that, on the hockey scene at least,” Clarke, 67, the greatest player in franchise history, said about the alumni-game sellout. “I mean, there are still some good players to watch like Lindros, LeClair and Briere. Those guys are still pretty good players, but there are a lot of us that aren’t. It was really fun, though.”

Lindros kidded that the fans got to watch old players perform “in slow motion.”

“It was great. It’s just that, when you get in front of that crowd that’s always behind you for five decades now,” he added. “All the guys had wonderful stories about the support they’ve gotten along the way and their own journeys and the team’s success. The fans are a really big part of it and you could feel it.”

Ed Snider would have been proud.