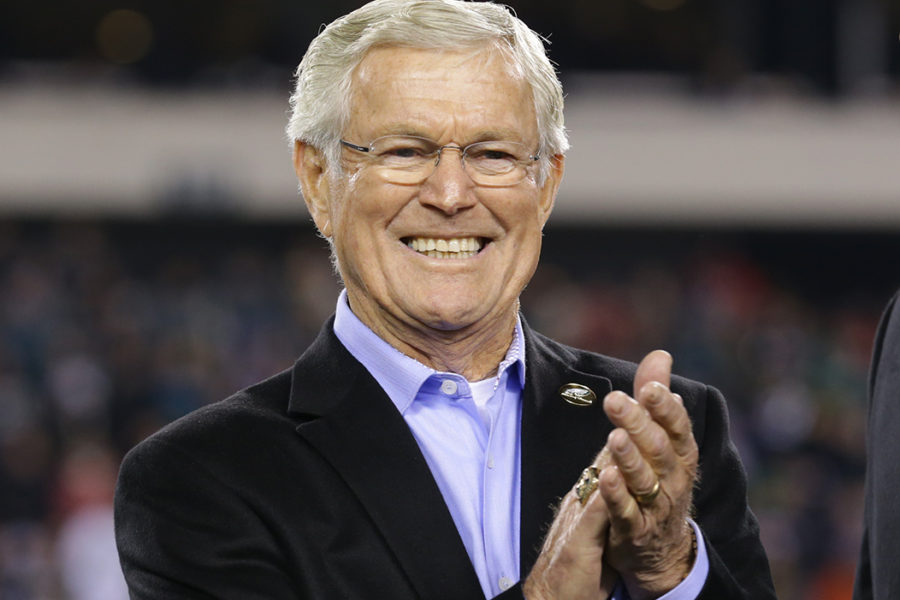

Philadelphia Eagles vs Green Bay Packers at Lincoln Financial Field

Ron Jaworski still remembers the in-season late-night calls he’d get from Dick Vermeil.

“I’d be home at 11:30 on a Thursday night and the phone would ring and it would be Dick,” the former Eagles quarterback said. “He’d say, ‘Put this tape in. I want you to see what we’re going to do in the red zone on Sunday. We’re adding these new plays.’ He wasn’t out. He wasn’t home. He was in the office putting plays together to help us win, make us better.’’

That was Vermeil. The workaholic coach who regularly put in 20-hour days and often slept on a sofa in his office during the season.

“Dick was very demanding of himself,” Jaworski said. “He had a very high bar individually. He wanted guys who understood you’d better have that bar raised high because we’re going to build a team here and we’re not going to lose. Get on the train or the train is going to run you over.”

Vermeil’s hard work paid off. He inherited a hapless Eagles football team bereft of draft choices when Leonard Tose hired him in 1976. One winning season in the previous 15 years. One! Five years after he arrived, they were in the Super Bowl.

That’s the good news. The bad news is Vermeil’s workaholic ways eventually got the best of him. Two years after the Eagles’ loss to the Oakland Raiders in Super Bowl XV, he walked away from coaching.

“By the end of ’81, I was having trouble getting over a loss,” said Vermeil, who will become the 28th coach in NFL history to be enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in August.

“My own negative is I’m a blamer of myself. I would spend too much time after getting beat thinking [about] what I should’ve done last week. It was interfering with what I should be doing to win this week.”

The Eagles opened the ’81 season with six straight wins. In mid-November, they were riding high at 9-2, one game ahead of the Cowboys in the NFC East. Another Super Bowl appearance seemed a real possibility.

Then they lost four of their last five and went one and done in the playoffs, suffering a stunning 27-21 wild-card loss to the Giants.

A couple of weeks later, Vermeil’s wife Carol was in a serious car accident. She fractured her right elbow and pelvic bone. Needed 50 stitches to close wounds in her head from shattered glass. Very nearly lost her left eye.

Then came the strike-shortened ’82 season. The players were out for 57 days. The league ended up cutting the regular season to nine games and holding a postseason “tournament’’ that included 16 of the 28 teams. The Eagles weren’t one of them. They lost their first four games after the strike and finished a disappointing 3-6.

In their first game back after the strike, they lost to the Cincinnati Bengals. As Vermeil began his post-game talk to the team, Eagles owner Leonard Tose interrupted.

“He takes a drag on his cigarette and says, ‘I have something to say,’’’ linebacker John Bunting said. “He says, ‘Why don’t you all do this city a favor and go back out on effing strike.’’’

Vermeil and his wife had a cabin in Clinton County, about 25 miles outside of Penn State. They spent a lot of time up there during the ’82 strike, which actually gave the Eagles coach a glimpse of life without football. And it wasn’t terrible.

“I remember driving up there and thinking, God, it feels so good not to have a stiff neck and strain on my back,” Vermeil said. “I never had a great ability to turn anything off. Now, I had no choice. And I enjoyed that feeling.

“Carol once told me that what I come home with [after work], what I have left [to give], isn’t very pleasant. And she was right. It was because I got so obsessed with what I was doing. And when you beat your own self up, you start believing it too.’’

After the strike, as the ’82 season dragged on, it became obvious to the people around Vermeil that he was struggling.

“Some of the team meetings late in the season at the [team] hotel, he would address the team, but it wasn’t the same guy,’’ Jaworski said. “He was very emotional. But it wasn’t the emotion of a coach. It was the emotion of a guy who was really struggling.’’

Late that season, Vermeil pulled into his parking spot at Veterans Stadium one morning and couldn’t get out of the car. A few days later, he was sitting at his desk and the same thing happened. He couldn’t get up to go to practice.

“When the strike ended and I went back to coaching, I just didn’t feel good about myself,” he said. “I said I owe these guys more.’’

The Eagles ended the season with a two-point loss at home to the Giants. A week later, Vermeil, then just 46 years old, resigned.

“The night before I stepped down, I said to Carol, ‘I know what I have to do, but I don’t know what to say,’’’ Vermeil said. “She said, ‘Why don’t you just say you’re burned out. She hadn’t read any books on it or anything, but that’s what had happened to me.’’

Burnout isn’t a terminal condition. If it was, Vermeil wouldn’t be getting a bronze bust in Canton.

He spent 14 years out of coaching, broadcasting NFL and college games for CBS and ABC before finally returning to the sideline in 1997 with the St. Louis Rams.

“The minute I walked into the (Rams) building, you could smell the losing,” Vermeil said. “They had lost more games in the ‘90s than any team in football.”

After going 5-11 and 4-12 in his first two seasons there, Vermeil and the Rams won the Super Bowl in 1999.

“When I went back into coaching, I knew I couldn’t be who I was,” Vermeil said. “It was a totally different game. I did a much better job of delegating and designating with the Rams.’’

Vermeil found out the hard way that he couldn’t work players as hard as he did when he was coaching the Eagles.

“I remember the first player rebellion that first year after we went full-gear the day after the final preseason game,” said Bunting, who was the co-defensive coordinator on Vermeil’s Rams staff. “It was a sweltering day. High humidity. We go into the locker room after practice and there are eight guys laid out on tables with IVs in their arms. The next day, player boycott. They go on strike. He eased up some. But it wasn’t until the third year that he really changed.’’

Vermeil might’ve won another Super Bowl with the Rams, but he retired after the ’99 season. Returned a year later to coach the Kansas City Chiefs for his longtime friend Carl Peterson, who will be his presenter in Canton next month.

He spent five seasons in KC. His 2003 team won 13 games.

“When he came to Kansas City, I could see he had changed a lot as a coach,” said Peterson, who had been Vermeil’s player personnel director with the Eagles. “His ways, his practices. He was more like their father. He was having the players over to his house and teaching them how to barbeque and drink wine.”

————-

2022 Pro Football Hall of Fame Inductee

Sam Mills

When Sam Mills enters the Pro Football Hall of Fame next month, Jim Mora will be the late linebacker’s presenter.

Mora coached Mills for 12 of his 15 professional seasons—three with the USFL’s Philadelphia Stars and nine more with the New Orleans Saints. He has called the five-time Pro Bowl linebacker the best player he ever has coached. Considering that he also happened to coach a fellow by the name of Peyton Manning, that’s high praise.

That said, Mora will be the first to admit that he initially had some serious reservations about Mills. In fact, if not for the persuasiveness of Vince Tobin, who was Mora’s defensive coordinator and linebackers coach with the Stars, he probably would have done the same thing the Cleveland Browns and CFL’s Toronto Argonauts did and cut Mills.

“I took the Stars job a couple of weeks before the start of training camp,” Mora said. “I didn’t know one guy from the other. All I knew about Sam was that he was 5-foot-9.

“Every night during camp, I would meet with Vince and the rest of our staff and have each position coach comment on and rank his players. Every night Vince would come in and have Sam ranked No. 1. I’d look at him and say, ‘Vince, we can’t play with a 5-9 linebacker. We just can’t. People will laugh at us.’

“And he’d say, ‘I don’t know what to tell you. He’s the best guy out there. If you want to get rid of every other linebacker we’ve got and start over, that’s fine. But I’m telling you he’s our best player.’”

Mills, who died of cancer in 2005 at the much-too-young age of 45, is being enshrined in the Hall of Fame this summer because of what he did during his 12 NFL seasons with the Saints and the Carolina Panthers.

But if not for the opportunity he got—and capitalized on—with the Stars, Mills never would have played a down in the NFL.

After getting cut by Cleveland and Toronto, Mills had pretty much accepted the fact that his pro football dream never was going to happen. With a wife and son to support, the former Montclair State star had accepted a teaching job at East Orange (N.J.) High School and was ready to get on with the rest of his life.

Then, in August of 1982, just before he was supposed to start his new teaching gig, the Stars, called him and invited him to try out for their team in the new spring league.

Mills went to the tryout and was offered a contract that guaranteed him nothing more than an invitation to training camp. He was so unsure that he waited two months before signing with them.

He already had a job that would allow him to feed his family. What if the Stars were no different than the short-sighted Browns and Argonauts? What if they also couldn’t get past his small size, no matter how well he played? Did he really want to go through that kind of disappointment again?

The guy who finally convinced Mills to sign with the Stars was Jim Garrett. Garrett, a longtime NFL coach and scout with several teams, convinced the Browns to sign Mills after he went undrafted out of Montclair.

Mills often worked out with other North Jersey prospects in the large yard at Garrett’s oceanfront home in Monmouth Beach, which was a stone’s throw from where Mills lived in Long Branch.

“I still remember Sam coming over to our house and telling my dad, ‘I’m going to give this thing up,’” said Garrett’s son Jason, who spent nine years as the Dallas Cowboys head coach. “My dad looked at him and said, ‘You can’t give it up yet, Sam. You can’t give it up. You have to figure out how to do this, how to convince them you’re big enough.’

“My dad urged him to go down to Philly and give it one more shot. Sure enough, he went there and ran with that opportunity and never looked back.”

Tobin eventually convinced Mora to look past Mill’s size, and he went on to become one of the best players the short-lived league produced. He racked up 592 tackles in three seasons. Was an All-USFL choice all three years. Led the Stars to three championship-game appearances and two league titles.

“Everybody thought Sam was an overachiever because of his size,” Mora said. “But he wasn’t an overachiever. He had a lot of ability and he achieved up to the level of that ability. He was the best player I’ve ever coached. He was an amazing guy.”

Led by Mills, the Stars had the best defense in the USFL. Led the league in points allowed three straight years—giving up just 11.3 points per game in 1983, 12.5 in ’84 and 14.4 in the league’s final season in ’85.

Center Bart Oates was Mills’ teammate with the Stars. Later played against him several times when both joined the NFL.

“I remember that first training camp with the Stars,” Oates said. “Nobody knew who Sam was at our first practice. But by the last practice, by the time we left Florida, everybody knew who he was. And it wasn’t long after that the rest of the league knew who he was.”

Glenn Howard played alongside Mills as the Stars’ other inside linebacker in their 3-4 scheme for three years. They became close friends.

“He played with a chip on his shoulder,” Howard said. “Even after the first year, when he was the league’s Defensive Player of the Year, he still played like he needed to prove himself to people.”

After the USFL folded, the Saints hired Mora as their head coach. He only took a handful of Stars players with him to New Orleans, but Mills was one of them. Mills quickly convinced his Saints teammates that his size wasn’t an impediment.

He became the lynchpin of their great defenses of the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. Finished his playing career with the expansion Carolina Panthers where he helped them make it to the NFC Championship Game in their second season of existence.

Mills played just three seasons for the Panthers but had such an impact on that franchise that owner Jerry Richardson had a statue of him erected outside the team’s stadium shortly after he retired as a player following the ’97 season.

“Mr. Richardson wasn’t the easiest guy to impress,” said Vic Fangio, who coached Mills with the Stars, Saints and Panthers. “But he loved Sam.”

Tobin spent seven seasons as the Chicago Bears defensive coordinator after the Stars folded. Coached another Hall of Fame linebacker, Mike Singletary, for all seven of those years. Singletary went into Canton in 1998 in his first year of eligibility.

Tobin has openly acknowledged that, in his mind, Mills was as good, if not better, than Singletary. Yet, it took Mills 19 years to make it to Canton. Well, better late than never.

“He went to heaven before he went to the Hall of Fame,” said Mills’ former Stars teammate and friend George Cooper. “That’s what God wanted.”