In 2003, Mitch Albom, the long-time sports columnist for the Detroit Free Press and a best-selling author, wrote a terrific novel called “The Five People You Meet In Heaven.”

The book is about an old man named Eddie who works as a mechanic at a seaside amusement park. He is killed trying to save a little girl from a falling ride. Eddie ends up in heaven where he meets five people who had a significant impact on his life.

I turned 67 in June and semi-retired in October after 39 years at the Philadelphia Daily News and Inquirer. I have no plans to put in my application for the afterlife any time soon.

But if I am lucky enough to hit the lottery and make it to heaven in about 30 years or so, I have a list of unforgettable people I’ve covered over the last four decades that I would definitely like to sit down with and interview again for the Pearly Gates Daily News.

Here are the two that are at the top of my list:

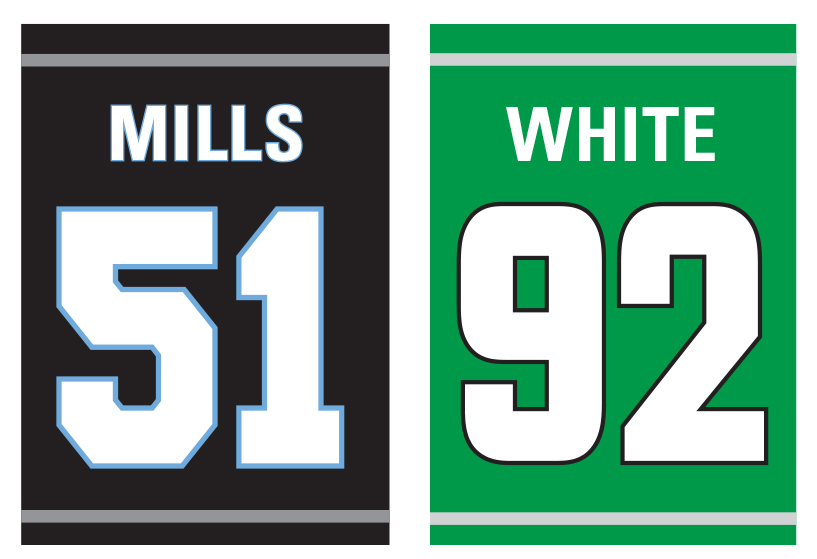

SAM MILLS

Sam Mills is the most inspirational player I ever knew. Every kid who’s been told he’s too short, too slow, too this or too that should acquaint themselves with Sam’s amazing story.

By the time I met him in 1983, he already had been given pink slips by the NFL’s Cleveland Browns and the CFL’s Toronto Argonauts.

Those rejections had nothing to do with a lack of ability. They had to do with a lack of height. Sam, an All-American linebacker at Montclair State, was only 5’ 9”, and the Browns and Argonauts didn’t think there was a place for a linebacker in pro football who was that small.

After Toronto cut him, he took a job teaching photography at a North Jersey high school. He thought his dream of playing professional football was over. Then a new spring league called the United States Football League was formed. One of the teams in that league, the Philadelphia Stars, called Sam and asked him if he’d be interested in trying out.

Sam actually had to think about it. He already had been disappointed twice. He wasn’t sure he wanted to shoot for the trifecta. But he ended up signing with them.

Sam ended up becoming the best defensive player in the USFL and leading the Stars to two league titles.

During the Stars’ first training camp in Deland, Fla., their head coach, Jim Mora, spent the first two weeks trying to convince his defensive coordinator, Vince Tobin, that they needed to cut Sam.

“We can’t have a 5’ 9” linebacker playing for us,” Mora kept telling Tobin. “People will laugh at us.” Tobin’s answer: “If you want to cut your best defensive player, then go ahead.

“My first impression of him?” Mora told me that first year. “I thought he was too short to play. And he doesn’t make up for it with exceptional speed. But the more you watch him, the more you like him.”

Mora eventually became a believer. When he took the New Orleans Saints’ head coaching job in 1986 after the USFL folded, he took Sam with him. Mills spent nine years there and three more in Carolina.

Was a five-time Pro Bowler. Led the expansion Panthers to the NFC Championship Game in their second season of existence.

Even though he played there for just three years at the end of his career, the Panthers erected a statue of Sam in front of their stadium.

Mills has been a finalist for the Pro Football Hall of Fame three times. Mora, who once wanted to cut Sam, now unabashedly calls him the greatest player he’s ever coached. So does Tobin, who coached Hall of Fame linebacker Mike Singletary with the Bears.

Sam died too young. He succumbed to intestinal cancer in 2005 at the age of 46. He was an assistant coach with the Panthers at the time.

I went to Charlotte and interviewed Sam seven months before he died. He already had lived a year longer than the cancer doctors had predicted at that point.

If I went there looking for a bitter, feeling-sorry-for-himself man, I would’ve been disappointed. But I had known Sam a long time. He never felt sorry for himself a day in his life. He was a fighter. And he fought the cancer right to the end.

“If God ain’t finished with me yet, nothing will happen,” Sam said to me that day. “You’ve just got to believe and keep on going. It certainly makes you appreciate life a lot more. I remember last year when we went out to Arizona for a game after I was diagnosed. You look around and you say, wow, what a beautiful country.

“You hear people talk about a movie coming out this winter or next spring and you think, man, I might not even make it that far. They talk about road projects and developments going up that should be done in 2005, and you say, I might not even see that.

“But that’s the way life is every day anyway. You don’t know whether you’re going to be around the next day. But something like this brings it to the forefront. I remember after I was diagnosed, thinking, they’re saying I might not even be around for my 45th birthday. But thank God I am.”

REGGIE WHITE

I’ve had the honor of being on the 48-member selection committee for the Pro Football Hall of Fame for the last 21 years. In 2006, I had the pleasure of making the presentation for Reggie White when the former Eagle was a finalist for the Hall in his first year of eligibility.

His selection was a formality. No one needed to be convinced Reggie belonged in the Hall of Fame. He was arguably the greatest defensive player who ever lived.

Since our selection meetings are marathons that have been known to last up to nine hours, I kept my sales pitch short and sweet. It was just five words: “Ladies and gentlemen, Reggie White,” I said.

He was a unanimous selection.

Reggie was not just a Hall of Fame player. He was a Hall of Fame human being. An ordained Evangelical minister who used football as his pulpit to spread the word of God.

But the man was not above vengeance. God help the poor offensive lineman who went after his knees. Or a cheap owner like Norman Braman who seemed to care more about the bottom line than winning and the welfare of his players.

Reggie spent the first eight years of his prolific 15-year career with the Eagles. Was the heart and soul of their late-80s/early-90s GangGreen defense, which was the best defensive unit in franchise history and one of the best in NFL history. Reggie spearheaded an unstoppable defensive line that also featured Jerome Brown, Clyde Simmons, Mike Golic and Mike Pitts.

During Reggie’s final four seasons in Philly from 1989 through 1992, GangGreen averaged an unbelievable 54 sacks and 47 takeaways per season and held opponents to 16.6 points per game.

The 6’ 5”, 295-pound White lined up at both tackle and end and was a nightmare for opposing offensive linemen. Played in 121 games for the Eagles and had 124 sacks. In 1987, he played in just 12 games because of the players’ strike and still had a league-high 21 sacks. Think about that for a second.

Reggie played two seasons in the USFL before signing with the Eagles three games into the ’85 season. Made an immediate impact in his first game, recording 10 tackles and two and a half sacks against the Giants.

“I had never seen anyone that big and strong who could move that fast,” said Arizona State head coach and former Eagles cornerback Herm Edwards, who played the last of his nine seasons with the Birds in Reggie’s first. “He was explosive. He drove blockers back like they were on roller skates.”

White was a named plaintiff in the NFL Players Association’s lawsuit against the owners that brought free agency to the league. As soon as free agency was implemented in 1993, White bolted Philly. Not because he disliked the city or the fans, but because he despised Braman.

He said he wanted to go someplace where he could do the most good for minority and underprivileged people. He said God would tell him where that would be.

When it ended up being in predominantly white Green Bay, Wisconsin with the team that offered him the most money, a lot of people called him a hypocrite.

But White followed through on his promise, helping both the black and white communities of Wisconsin and spreading his ministry there. He also helped turn around the Packers. They made the playoffs all six years Reggie played for them. Made it to the NFC Championship Game his third year there and won the Super Bowl in his fourth. In his final season with the Packers in ’98, he had 16 sacks.

“Reggie was no phony,” his wife Sara said in her acceptance speech for her husband at his posthumous Hall of Fame induction in August of 2006. “He stood for what he believed in.” Indeed he did.

I interviewed Reggie dozens of times during his career, both in Philly and Green Bay. He was one of the most honest and candid players I’ve ever known. Ask him a question, any question, and he would give you a truthful answer, even if it got him into trouble sometimes.

I still remember flying to Green Bay to interview him the season after he signed with the Packers. Talked to me for 45 minutes. Admitted he never would have left Philadelphia if Jeff Lurie had bought the Eagles from Norman Braman a year earlier.

I was stunned when I heard the news of Reggie’s sudden death the day after Christmas in 2004. It was one of those tragedies where you will always remember where you were when you found out.

I was at the Philadelphia airport getting ready to board a plane for an Eagles Monday night game in St. Louis against the Rams when my office called to tell me.

Like Sam Mills, Reggie died too young. He had finished his football career but had so many grand plans for his post-football ministry.

“If life had a Hall of Fame for people who were important in society, let me be so bold as to say my dad would be in the life Hall of Fame,” Reggie’s son Jeremy said in 2006 when he presented his dad for induction in Canton.

“His passion for God, his love for his family and community, and his dedication toward making the world a better place would at least get him nominated.”