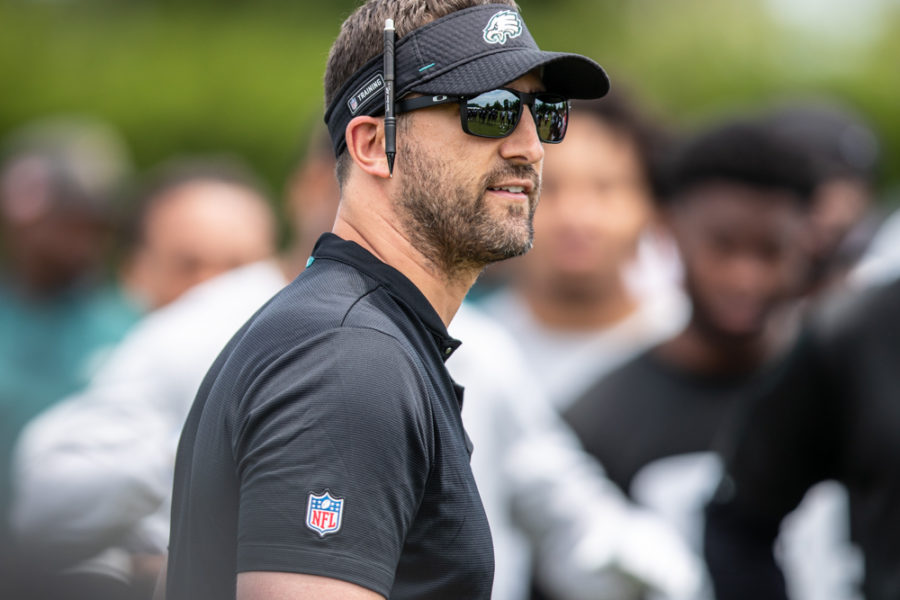

Nick Sirianni

In some ways, Eagles coach Nick Sirianni has a tough act to follow, replacing the only man to ever lead the Eagles to a Super Bowl championship.

In other ways, his first year, which is in full swing, should be pressure-less because expectations were low when the season started, and because most of the Eagles coaches who preceded him didn’t exactly look like the second coming of Vince Lombardi in their initial seasons with the Birds.

Which shouldn’t be surprising because when a new coach comes in, it’s usually because he is inheriting a bad situation.

From Philadelphia Eagles

Going back to 1976, many Eagles coaches have struggled mightily in their first season with the team.

Heck, even the great Dick Vermeil went 4-10 in his first season in ’76. Marion Campbell’s Eagles were 5-11 after he took over in 1983—and it was a sign of things to come. It took Buddy Ryan until his third year to get the Eagles into the playoffs, and his first team was a miserable 5-10-1 in 1986.

There were some exceptions to the Welcome to Philly Blues. Odd exceptions. In their first seasons in Philadelphia, the unremarkable trio of Rich Kotite, Ray Rhodes, and Chip Kelly directed the Eagles to 10-6 records in 1991, 1995, and 2013, respectively. (The rest of their coaching careers were, ahem, not too memorable.)

Growing pains, however, have been the norm for new Eagles coaches as the players get acclimated to their system and their personality.

Andy Reid, who got the Eagles into the playoffs in nine of his 14 seasons and later won a Super Bowl in Kansas City, is among those who had an inauspicious start: a 5-11 record in his first year in Philly in 1991. And Doug Pederson’s Birds went 7-9 in his first year in 2016 before improbably winning the Super Bowl the next season.

All of which means Eagles fans should be patient with Sirianni. Hope for the best this season, but know that the lows will probably outnumber the highs. Also, know that good days should be ahead.

“I’m excited for him,” Vermeil said just before the season started. “He does things differently and contrary to my philosophy, but when I see someone doing things differently, I don’t evaluate it as them being wrong and me being right. It’s just different, and I watch the way it works.”

In Sirianni’s first season, the Eagles have had “much shorter practices,” Vermeil said, comparing them to his coaching days. “And he gives veterans the day off, and that kind of stuff. That was not part of my way of thinking in building football teams, so I’m anxious to see how it works because then I learn something. And a lot of that is controlled by the Players’ Association today—days off and the shorter practices and dropping OTA’s (organized team activities) because the players didn’t want them.”

Vermeil, who is the coaching finalist for the 2022 Pro Football Hall of Fame class, paused.

“My old motto was, ‘If you’re going to make them happy, buy them beer. If you want to make them better, make them sweat,’” he added.

So who is Nick Sirianni and how did he unexpectedly land on the sideline of Philadelphia’s most famous sports team?

He is personable, enthusiastic, and likes to learn about his players’ personal lives.

After he was named the Eagles coach, Sirianni phoned his players in the offseason. He didn’t want to just talk about football; he wanted to know what made them tick, what they enjoyed doing off the field.

“He wanted to build relationships,” Eagles running back Miles Sanders said early in training camp.

Sirianni comes from a family of teachers, is the son of a legendary high school football coach and has close ties to his upstate New York community. He paid his dues by spending 12 years as an NFL assistant before being named the Eagles head coach when he was 39. That made him the youngest Eagles coach since Vermeil was hired when he was only a few months younger in ‘76.

If the Eagles get back to the promised land, it will be because Sirianni learned from the man perhaps most responsible for the lone Super Bowl triumph in franchise history, Frank Reich. Reich, of course, was the Eagles’ offensive coordinator in 2018 when they beat Tom Brady and New England, 41-33, and won Super Bowl LII with backup quarterback Nick Foles leading the way.

Reich was the Chargers’ offensive coordinator when Sirianni was there as a quarterbacks coach. When Reich became the head coach in Indianapolis, he named Sirianni to direct the offense, saying he knew if he ever had the chance to lead a team, “he would be the guy I want to be my coordinator.”

During Sirianni’s three years as Indy’s offensive coordinator, the Colts were solid. They were 30th in the league in points the year before Sirianni and Reich arrived. They ranked fifth, 16th and ninth in points in the three years Sirianni and Reich were together, making the playoffs twice in that span.

“He’s football smart,” Reich said of his prodigy.

After the Eagles hired Sirianni, Reich called the new coach “brilliant,” and said he was a “natural leader” who held players accountable.

“He’s been preparing for this his whole life,” Reich said in an interview on the Eagles’ website.

Reich called Sirianni his “right-hand man” on play-calling, and said he was the “driving force in everything we did.”

But was he prepared to coach under a microscope, in a football-crazed city that fills the radio airways IN THE SUMMER with passionate talk about who should be the backup right guard?

We shall see.

When Sirianni was hired, Twitter went atwitter. Naturally.

One delighted fan tweeted a photo of Tony Soprano and his boys, saying it was “Nick Sirianni and his coaching staff.”

Another fan said the hiring prompted him to make garlic bread and meatballs.

A woman noted that “my meeting was pushed back and my team hired a young hot Italian coach. Yes, I’m having a fantastic day.”

There were also cynical views, of course.

Sportswriter Frank Fitzpatrick, who has since retired from The Inquirer after a distinguished career, tweeted that Sirianni “is from the same hometown—Jamestown, N.Y. … as Lucille Ball. Won’t be long till he’ll have some ‘splainin to do.’”

Comparing Sirianni to Vermeil isn’t fair, but it’s inevitable because they both were hired at the same age. Both are comfortable showing their emotions—Philly kind of guys—and both try to get close to their players. It’s tempting, then, to compare Sirianni’s path—wherever it may lead—to that of the legendary former Eagles coach who is now a California winery owner.

Vermeil, whose teams began an upward trend after quarterback Ron Jaworski was acquired from Los Angeles for tight end Charle Young in 1977, got the Eagles to the Super Bowl in his fifth season. (Vermeil was familiar with Jaworski because he was on the Rams’ coaching staff when they drafted him. “I knew he was a tough-minded kid from the East, and that he would fit in this community,” Vermeil said.)

Eagles fans, mindful the (aging) team went just 4-11-1 last season and has many question marks, would probably accept a similar fate under Sirianni—a Super Bowl finalist in five years—with open arms.

Vermeil’s team struggled mightily in his first year in Philadelphia, matching the 4-10 record of the previous season and missing the playoffs for the 16th straight time.

Philly was the center of attention during America’s 200th birthday in 1976, but the Eagles didn’t do much celebrating. “The Philadelphia fans are the most loyal in the country,” Vermeil told his team in that preseason, “and they deserve the best. … The Eagles will never be taken for granted this season.”

But Mike Boryla threw five more interceptions (14) than touchdowns (9) and finished with an unsightly 53.4 quarterback rating as the Birds’ offense, despite the presence of future Hall of Fame wide receiver Harold Carmichael (5 TDs), struggled mightily. The Eagles were outscored, 286-165.

Gradually, they got better.

“I had been a head coach in high school, junior college, and college, and I had been an offensive coordinator in the NFL and a special teams coach,” Vermeil said. “So even though I was young, I had experience and that helped me. Nick has some of those experiences, but never as a head coach. I wish him well. I’m pulling for him. I’m an Eagles fan. I’m not an Eagles critic. I never want to criticize someone for a mistake that I made three times myself.”

Vermeil’s early teams improved steadily—from 4-10, to 5-9, to 9-7, to 11-5, to 12-4 and a spot in Super Bowl XV.

Asked what he recalled about his first year in Philly, Vermeil was quick with a reply.

“I remember not having any draft choices,” he said, mindful the Eagles’ highest picks in his first three years were in the fourth, fifth, and third rounds, respectively. “I remember putting a real, real strong emphasis on those later picks. And my guys did a great job with it. Carl Hairston was drafted that year (1976, seventh round) and Herb Lusk (10th round) came in that year. We didn’t have a first-round pick until 1979 (Jerry Robinson). That was tough. And what was also tough for me was that we had six preseason games and I don’t think we won one (he’s right), and we had a long training camp. A lot of long days and a lot of pad work and a lot of development work, trying to build what they now call a culture.”

Now it’s Sirianni who is trying to turn around the Birds’ culture. This will help: The Eagles potentially have three first-round draft picks next year because of trades.

Sirianni will make adjustments, no doubt, like Vermeil did in his first season.

In Vermeil’s initial year, for instance, he changed his practice routine early in the season. Instead of alternating practice days for the offense and defense like he did between the first few games, “we began doubling up and had offensive days and defensive days EVERY day,” Vermeil said. “We stayed on the field longer and harder and we sent them into games more prepared—and they started getting better. We didn’t have first-round picks coming up to replace them.”

Sirianni, like Vermeil, is a people person. Both are passionate about their profession and yet humble.

“He sounds like a good communicator,” said Vermeil, who was a big admirer of Pederson. “I’m excited about him. I would just tell him to be yourself, be demanding, and be honest.”